I find writing about short story collections a bit intimidating. I’ll usually write a post here saying that the collection is ok and then quickly forget the stories until I read something else that reminds me of one of them. In some recent posts about short story collections, I have been including a table on the stories with a summary and/or my thoughts. I’m not sure if people are interested in these, but they help me remember.

I recently read Brian McNaughton’s Satan’s Surrogate. It’s not a particularly good book, but it’s full of allusions to other works of weird fiction, including Robert W. Chamber’s The King in Yellow. I read and reviewed that collection a few years ago, and although I knew I had enjoyed it, I couldn’t remember much about it other than the fact that it featured The King in Yellow, a non-existent book that was supposed to drive people mad. I also recalled that it had distinct sections and that only the first section dealt with the really weird stuff. I went back to read my post on it and discovered that I had included summaries on all of the stories in the book except the first four, the really interesting ones. (I also discovered that I had reviewed a second book by Robert W. Chambers that I had entirely forgotten about. I don’t know if I’m going senile or if I’ve just read too many books.)

A few weeks ago, I got sick. I actually vomited for the first time in maybe 20 years. I get a few colds every year, but I honestly cannot remember the last time I had a tummy bug. I didn’t realise that vomiting actually hurts and that I’m not capable of doing it quietly. Luckily enough, I vomited in the morning, before I had actually eaten anything, so it was just my cup of tea (and a single green bean from the night before) that came back up. Anyways, I was bedbound for a couple of days, and reading Satan’s Surrogate seemed like too much work. I wanted an audiobook, and I realised that I’d easily be able to find an audiobook copy of The King in Yellow. I only bothered with the first four stories, but I really enjoyed revisiting them.

The Repairer of Reputations

This is quite a complicated tale. It’s set in 1925 which was 25 years in the future at the time that it was written. It’s a little dystopian and involves the unveiling of government funded suicide booths, but it’s a horror story at its core. The narrator reads The King in Yellow while recovering from a head injury and ends up involving himself in a murderous conspiracy. His best friend is basically a professional blackmailer, and together they plan to seize control of the world. The plan doesn’t work out.

I read it and reread it, and wept and laughed and trembled with a horror which at times assails me yet. This is the thing that troubles me, for I cannot forget Carcosa where black stars hang in the heavens; where the shadows of men’s thoughts lengthen in the afternoon, when the twin suns sink into the lake of Hali; and my mind will bear for ever the memory of the Pallid Mask. I pray God will curse the writer, as the writer has cursed the world with this beautiful, stupendous creation, terrible in its simplicity, irresistible in its truth—a world which now trembles before the King in Yellow.

The narrator did suffer a brain injury, but his madness was certainly exacerbated by reading The King in Yellow. Vance, their hitman, also went insane after reading the book. It is not explicitly stated, but it seems to me that Chambers wanted his readers to believe that the legalisation of suicide was somehow influenced by the popularity of the awful tome.

The Mask

Two artists love the same girl. One of the guys reads The King in Yellow and then discovers a way to turn living creatures into statues. It is not explictly stated that his discovery was inspired by his reading. He starts off putting little creatures into his magic potion, but things get messy and the girl that everyone loves ends up in the puddle. I had completely forgotten the previous story, but I remembered what was going to happen at the end of this one quite soon after beginning it. It’s quite good, but The King in Yellow plays a fairly minor role. Characters from the play show up in the narrator’s fever dreams, but he has only ever flipped through its pages, so he ultimately retains his sanity.

I thought, too, of The King in Yellow wrapt in the fantastic colors of his tattered mantle, and that bitter cry of Cassilda, “Not upon us, oh King, not upon us!” Feverishly I struggled to put it from me, but I saw the lake of Hali, thin and blank, without a ripple or wind to stir it, and I saw the towers of Carcosa behind the moon. Aldebaran, The Hyades, Alar, Hastur, glided through the cloud rifts which fluttered and flapped as they passed like the scolloped tatters of The King in Yellow.

In the Court of the Dragon

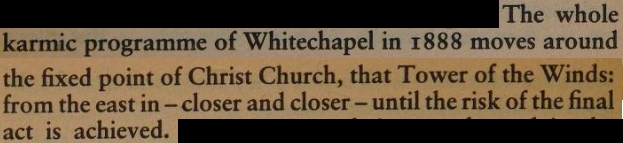

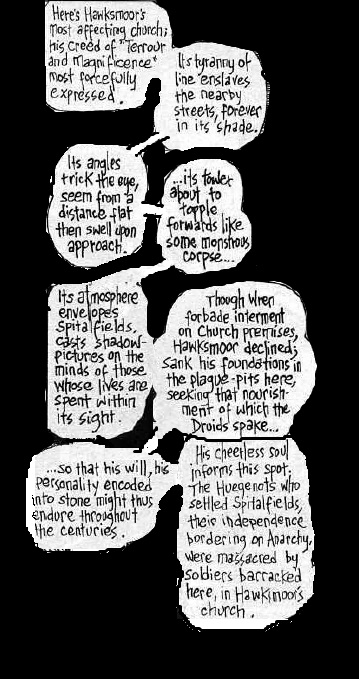

A lad gets bored during a church service, and he starts daydreaming about getting chased around town by the grumpy looking church organist. Part of the reason he is attending church is that he recently read The King in Yellow, and he finds the peaceful atmosphere in the church relieving. When he awakes from his daydream, he is transported to Carcosa and confronted by the Yellow King himself.

And now, far away, over leagues of tossing cloud-waves, I saw the moon dripping with spray; and beyond, the towers of Carcosa rose behind the moon.

Death and the awful abode of lost souls, whither my weakness long ago had sent him, had changed him for every other eye but mine. And now I heard his voice, rising, swelling, thundering through the flaring light, and as I fell, the radiance increasing, increasing, poured over me in waves of flame. Then I sank into the depths, and I heard the King in Yellow whispering to my soul: “It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God!”

The Yellow Sign

A painter is disturbed by a new watchman that has started working at the church opposite his house. This watchman’s face is so disgustingly ugly that it causes the painter to ruin the picture he is painting. The model who is posing for him falls in love with him, but she is haunted by strange dreams of the painter in a glass coffin. She gives him a strange piece of black jewelry as a gift. When the painter hurts his hands and can’t paint, the model hangs around his house. She finds a copy of The King in Yellow even though the painter did not own a copy because his friend, the narrator of The Repairer of Reputations, had gone mad after reading it. It is never explained how the book got into his house. Maybe the creepy watchman put it there.

I had always refused to listen to any description of it, and indeed, nobody ever ventured to discuss the second part aloud, so I had absolutely no knowledge of what those leaves might reveal. I stared at the poisonous mottled binding as I would at a snake.

Both the painter and his model end up reading the book. Soon thereafter, their dreams come true. The disgusting watchman breaks into their home and tries to steal the onyx clasp. Nobody survives. When the narrator realises what is happening he says,”I knew that the King in Yellow had opened his tattered mantle and there was only God to cry to now.”, but apparently the original text read,

I knew that the King in Yellow had opened his tattered mantle and there was only Christ to cry to now.

Apparently the publisher changed this so it wouldn’t offend Christian readers.

There are other stories in the collection, but none of them deal with The King in Yellow or Carcosa, and I’ve discussed them already. I think The Yellow Sign is probably my favourite out of these 4 stories. All four contain small references to other stories in this collection, but each tale works by itself. The references to The King in Yellow are maddeningly sparse, and you’ll want to read all four of these stories to get all the details. I reckon it’s what Chambers doesn’t say about this strange text that makes it so appealing. From what little he reveals, I have deduced that the play is about a shabbily dressed King who creeps out two Carcosian ladies called Cassilda and Camila.

Camilla: You, sir, should unmask.

Stranger: Indeed?

Cassilda: Indeed it’s time. We all have laid aside disguise but you.

Stranger: I wear no mask.

Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda.) No mask? No mask!

The King in Yellow, Act I, Scene 2.

I thought, too, of the King in Yellow wrapped in the fantastic colours of his tattered mantle, and that bitter cry of Cassilda, “Not upon us, oh King, not upon us!”

I remembered Camilla’s agonized scream and the awful words echoing through the dim streets of Carcosa. They were the last lines in the first act,

What the Hell is that creep up to?

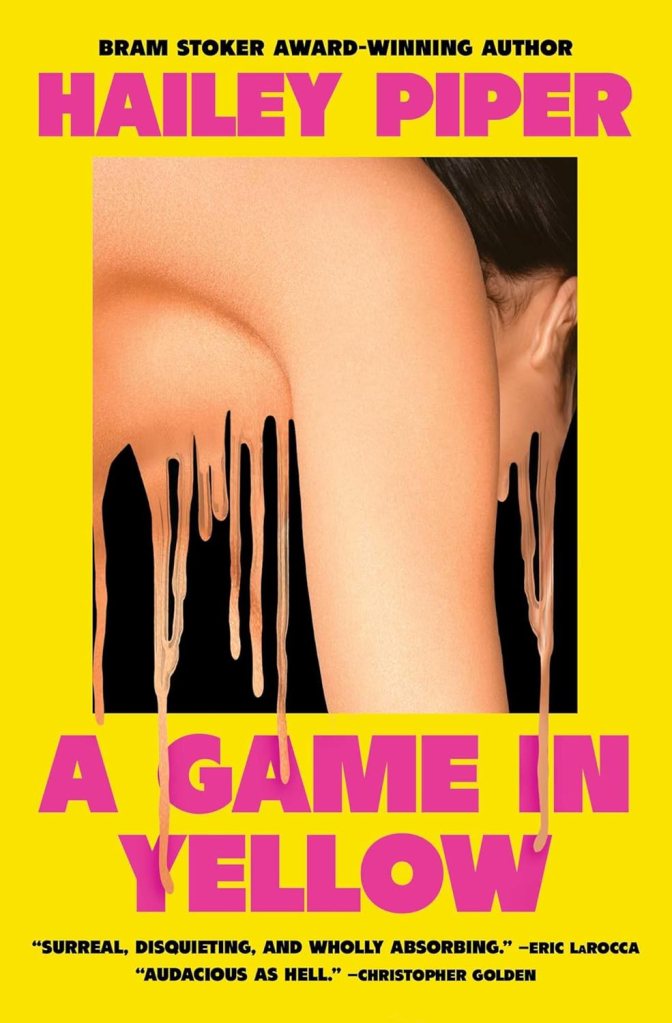

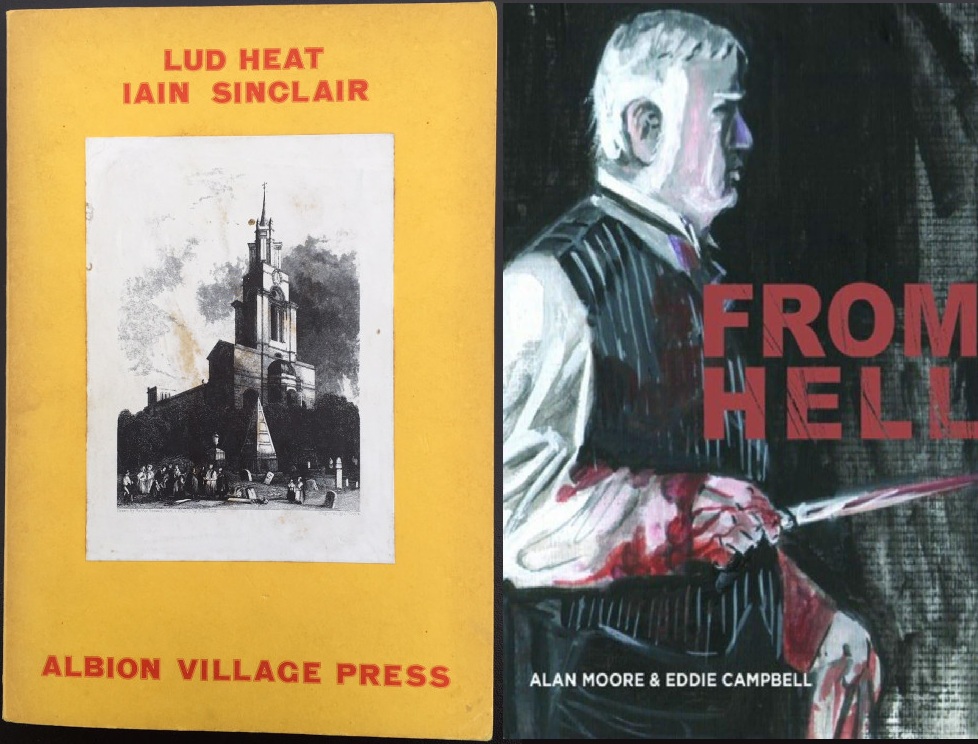

I know I mentioned it before, but there is something embarrassingly exciting about a creepy book that doesn’t exist. One of the characters in Satan’s Surrogate actually attempts to write a play with a similar title, but he isn’t successful. I quite enjoyed rereading these 4 stories by Chambers. Nothing else I’ve read by him comes close to them, but their atmosphere and allusions to the maddening and mysterious Yellow King are enough to ensure that Chambers is remembered as a master of weird fiction.