Only yesterday, I finished reading Richard Kaczynski’s Perdurabo, the monumental biography of Aleister Crowley. I had intended on publishing a review of that book today, but seeing as though it’s Saint Patrick’s day, I thought I should post something relating to my native Ireland. Last year, I posted Aleister Crowley’s poem “Saint Patrick’s Day, 1902”. It was my second post discussing Crowley’s strange attitude towards Ireland. While reading through Kaczynski’s biography of the Great Beast, I found another interesting link between Crowley and the Emerald Isle.

In July 1923, Crowley had an article titled “The Genius of Mr. James Joyce” published in New Pearson’s Magazine. Crowley discusses both Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man and the then recently published Ulysses, showering both novels with lavish praise. When reading Crowley, one should always consider the possibility that he’s being insincere, but that’s clearly not the case here. It’s not hard to see how Crowley would be interested in a character like Joyce; both men were leaders in their fields, sexual deviants, largely misunderstood, and victims of censorship. (Although the two men never met, several people, including Kaczynski and Robert Anton Wilson, have pointed out similarities in their writing.)

Here then, in its entirety, is Aleister’s article on Jimmy:

The Genius of Mr. James Joyce

Within the last twenty years a new form of literature has been evolved, the novel of the mind. I mean by this a story where what men do is described only as the outcome of what they think and feel and believe, and where the focus of interest is in their thoughts rather than in their acts. This literature is still in its experimental stage, and a majority of the novelists fail because they think it is enough to observe correctly, and so produce pathological studies rather than works of art. Their work is interesting because it is concerned with reality, but for the most part it is indifferent literature, because the reality has not been worked into proper shape. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that the further the majority of these writers probe into the mind of man, the further they depart from artistic creation.

My Wyndham Lewis’ novel Tarr is a case in point. It is one of the most interesting books written within the last ten years. It is a book that opens a secret cupboard and displays the contents with an observation that compels our admiration, but our chief interest is in watching the cat let out of the bag. All sensitive men are compelled to plead guilty to the indictment, but there is little indication that the author is interested in style for its own sake, and that his purpose would not have been as well served by an essay on the hatred of human beings for human nature.

This form of writing has been saved, by the genius of Mr. James Joyce, from its worst fate, that of becoming a mere amateur contribution to medical text-books.

Every new discovery produces a genius. Its enemies might say that psych-analysis—the latest and deepest theory to account for the vagaries of human behavior—has found the genius it deserves. Although Mr. Joyce is known only to a limited circle in England and America, his work has been ranked with that of Swift, Sterne, and Rabelais by such critics as M. Vatery, Mr. Ezra Pound and Mr. T. S. Eliot.

There is caution to be exercised in appraising the work of a contemporary. When we like him at all, we are inclined to like him too much, because we are in unconscious sympathy with his presentation of life, and are incapable of judging his work impartially. I am convinced personally that Mr. Joyce is a genius all the world will have to recognize. I rest my proof upon his most important book Ulysses, and upon his first novel, A Portrait of the Artist as Young Man, and on such portions of Ulysses as have appeared. Before these he wrote two books, Chamber Music (The Egoist Press, London), a collection of most delicate songs, and Dubliners (Grant Richards, London), sketches of Dublin life distinguished by its savage bitterness, and the subsequent hostility it excited. The Portrait when it appeared was hailed as a masterpiece, but it has been boycotted by libraries and booksellers for no discernible reason other than the fact that the profound descriptions tell the truth from a new, and therefore to the majority a disturbing, point of view.

The book is the history of the infancy, childhood, and adolescence of a high-school boy, Stephen Daedalus. While he is little his people are prosperous gentle folk, by the time he is grown up they are living in a Dublin slum. In a magnificent early chapter his family sit round their rich Christmas Dinner. It is the time of the Parnell tragedy, and every person there takes a different view of it with an equal passion, and their dispute rises with matchless intensity until Stephen’s father is left alone at the head of the table and cries and says, “Parnell, my dead king.”

Stephen goes to a Catholic public school, and his young body and his young beliefs drive hell into him, and he leaves school and goes to college and finds his nature unchanged. He grows up in love with absolute beauty, and obsessed with the obscenity of life. He is tortured so soon as he is able to perceive the conflict of the body and the soul, the excremental animal and the image of God.

The book is written with the utmost delicacy and vigor. When Stephen is a baby, Mr. Joyce selected the exact incidents that would impress the hardly conscious minds in such a way that the reader finds that his own infantile memories are astir. He recalls his own mind when it was incapable of synthesis and conscious only of alternation between nourishment and excretion. Gradually the child becomes aware of the relation between one thing and another, with adolescence his consciousness becomes complete, and the struggle of the individual to express and reconcile himself to life begins. As his mind changes Mr. Joyce changes his style, the unperceiving mind is shown so that the actual texture of its unperceptiveness is felt, an incomplete thought is given in its incompleteness. But when Mr. Joyce leaves his characters to their stream of unsorted perceptions and speaks for himself, he write classical English prose with the particular beauty proper to a new master. Stephen is walking on the cliffs of Dublin bay, and looks over to the town and sees—

“as a scene, or some dim areas, old as man’s weariness the image of the seventh city of Christendom was present to him across the timeless air, not older, not more weary, nor less patient of subjection than in the days of the thingmote.”

The end of the Portrait leaves Stephen still at Dublin University. He is the eldest, a swarm of brothers and sisters sit round the table and drink tea out of jam pots. His mother “is ashamed a University student should be so dirty, his own mother has to wash him.” He is the poorest of poor students, the most gifted, proud and perverse. We leave him, knowing that there is worse in store for him and turn to Ulysses.

Ulysses (The Shakespeare Book Co., Paris—by subscription), as the title suggests, is another Odyssey of a small Jewish commercial traveler round about the Dublin streets on one day.

About him there unwinds the most extraordinary procession of his friends and acquaintances from one public house to the next, and among them is Stephen, his father gone in drink, Buck Mulligan, a horsey “tough,” barmaids, the Rev. Father Conmee S. J. Stephen’s little sister buying a French grammar for a penny, maid-servants, loafers, business men, all passing and talking and dreaming, and observed and set down to what seems the last possible point of human observation.

A great part of the book is passed in a public house where the scenes of the Odyssey are represented by two barmaids standing behind a barrier of whiskey-bottles which contain, as Mr. Joyce observes, “orient and immortal wheat standing from everlasting to everlasting.”

Stephen is now a school master, reading Lycidas over the heads of a class of indifferent children. He is now a quite subsidiary character. It is in Mr. Bloom that the essence of the book lies.

The disreputable, snobbish Catholic world sees in Mr. Bloom a commercial traveler of a despised race. Mr. Bloom sees himself as a lover, a poet, a gourmet, and a man-of-the-world. Yet he is an acute observer of himself, he takes himself into his own confidence, and it is infinitely entertaining to overhear him. It is also shocking and startling. His Odyssey is between his home, some shops, a cemetery and a public-house, in a trance on foot. In the beginning he buys a piece of soap, “sweet lemony wax,” and the part taken by that piece of soap in his trouser pocket is given its exact proportion. It has a life-history of its own, a “Little Odyssey.”

I have no space to enter upon the real profundity of this book, or its amazing achievement in sheer virtuosity. Mr. Joyce has taken Homer’s Odyssey and made an analogy, episode by episode, translating the great supernatural epic into terms of slang and betting slips, into the filth, meanness and wit and passion of Dublin today. Then the subtle little alien is shown exploiting, as once the “Zeus-born, son of Laertes, Odysseus of many wiles” exploited, the ladies and goddesses of the “finest story in the world.”

At present Mr. Joyce is all but unknown except to the inmost ring of English and French lovers of the arts. In his own country prejudiced Dublin opinion is making a determined effort to boycott him. It would certainly reflect no discredit on the Commonwealth of Australia if she were to be one of the first to recognize a writer who will in time compel recognition from the whole civilized world.

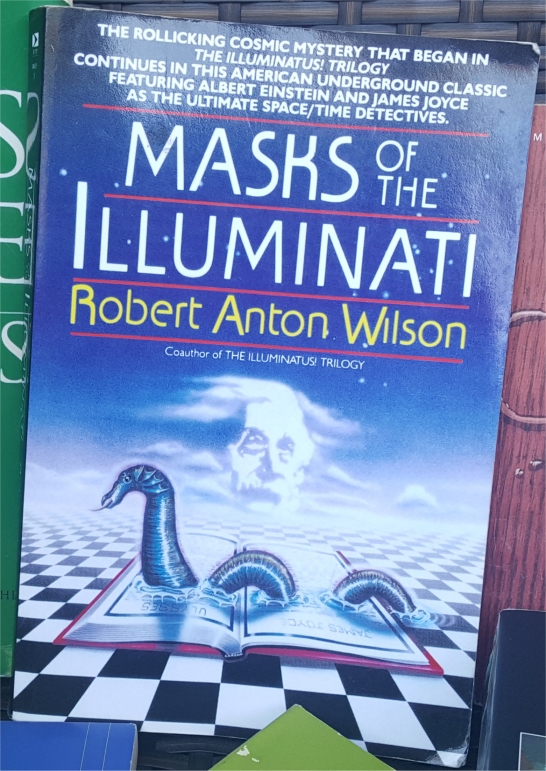

Of course, this isn’t the first time I’ve encountered these lads in conjunction with each other. Both Aleister Crowley and James Joyce appear as central characters in Robert Anton Wilson’s Masks of the Illuminati.

Expect more on Crowley here soon. I should have the review of Perdurabo ready for next week.

Masks of the Illuminati – Robert Anton Wilson

Masks of the Illuminati – Robert Anton Wilson I got about 6 pages into Finnegan’s Wake before giving up.

I got about 6 pages into Finnegan’s Wake before giving up.

Meeting the Other Crowd, The Fairy Stories of Hidden Ireland – Eddie Lenihan

Meeting the Other Crowd, The Fairy Stories of Hidden Ireland – Eddie Lenihan